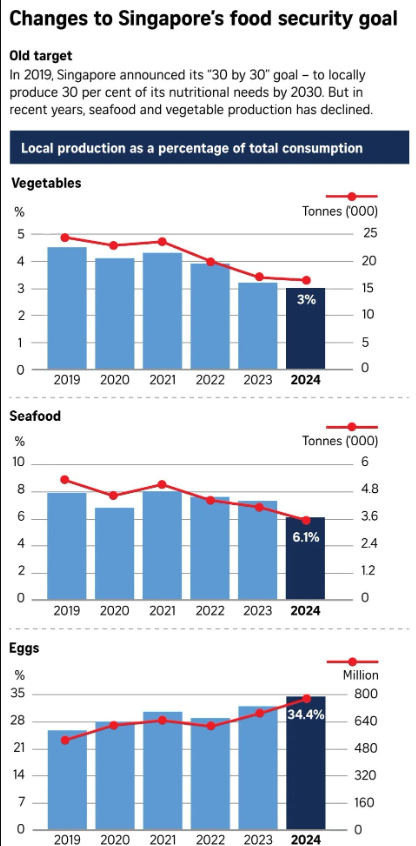

Singapore’s “30 by 30” ambitions have served as the guiding principles for the country’s food security strategy for decades. The goal was clear from the beginning: by 2030, the nation would be producing 30 percent of its nutritional requirements in-country, compared with less than 10 percent that it had achieved. It was audacious, imperative and symbolic of a small country’s determination to increase resilience to global food-supply shocks.

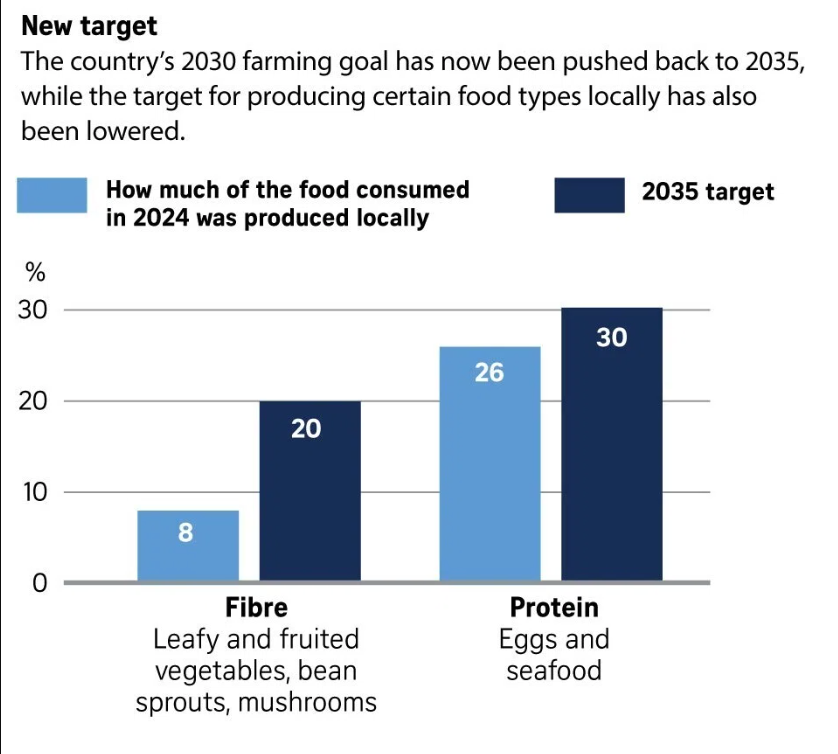

But amid a changing world — economic, environmental and technological, Singapore has turned its gaze back around and determined how the original target is relevant in the realities of the present. There is a more nuanced “30 by 30” direction, with its focus on strategic adaptability rather than hard-coded percentage numbers.

The change comes not as a retreat from the country’s plans of food resilience, but rather as a reformulation of how Singapore plans to build sustainable agri-food systems over the long term. The change recognizes the barriers to the scaling up of food production in an urban country of land, energy, local labour and technological innovations.

Still, it underscores an enduring determination to channel the agricultural industry toward innovation and efficiency. This change of target probably reflects a more realistic and sustainable way of doing things—one which alters perceptions and doubles down on what the world can actually do.

Why the Original “30 by 30” Target Necessitated Revamping

Singapore’s “30 by 30” vision was widely embraced and became known as a guiding philosophy regarding policy, investment, and industry. But a mix of global and local pressures in recent years brought a rethinking of the original framework. The first challenge relates to the availability of land.

Singapore’s land use remains limited despite the growth of vertical farms and high-density aquaculture systems. Food production must compete with industrial growth, housing needs, transportation infrastructure, and future land reserves. Scaling local production capacity at 30% of the nutritional requirements would require a lot more land or innovation that has until now proved not viable in a commercial sense.

Another challenge is energy intensity. Indoor farming solutions, although efficient and weather-tolerant, rely on large amounts of energy for lighting, cooling and water movement. Commercial operators contend with cost pressures that can impede long-term viability with energy prices in the world oscillating over the last few years.

Food grown by high-energy systems faces high prices that are costly to public consumption at a local level. The third issue is labour constraints. Advanced farming needs specialist operators with expertise in robotics, biotechnology, water systems, and environmental controls.

Singapore’s labour market is already stretched across many industries. And adding to the complexity was the challenge of scaling a large agri-food workforce in a short period of time. These realities don’t detract from the ambitions of “30 by 30,” but they help explain why Singapore has pivoted away from relying on a fixed percentage model towards an adaptable, resilience-focused framework that values capacity, innovation, and responsiveness over hard quantity measures.

A Capability Focused Agrifood Roadmap

Singapore is moving the focus of the new approach to developing capacity instead of achieving a strict number of per unit production quotas. And that means changing the discussion from “how much food we produce” to “how prepared we are in the event of disruptions to supply chains.” Establishing surge capacity is one of the primary paths, so farms can ramp up production quickly in emergencies.

Instead of pumping out 30% year-round, this can sometimes be ineffective—the concern is: do companies have the technological and infrastructural means to turn up those production lines when worldwide supply falls off? Yet at the same time there is a new wave of effort towards energy-efficient farming technologies.

The new roadmap places greater reliance on solutions that lower resource usage than solely on controlled-environment farms. Such applications include hybrid greenhouse systems, climate-optimized crop selection, better farm automation, and less dependence on high energy artificial lighting. At the same time, Singapore is also developing a stronger R&D ecosystem.

There is a growing body of research in areas such as sustainable aquaculture, high-yield cultivars, waste-to-nutrient systems, and precision agriculture technologies. These developments contribute to future-proofing the industry with local production becoming more efficient and commercially viable.

The updated “30 by 30” objective effectively reconceptualizes the target with regard to flexibility, capacity, and long-term resilience rather than a fixed nutritional goal.

What This Means for Local Farmers and Agri-Food Firms

The recalibrated roadmap remains a huge opportunity for farms, food-tech startups, infrastructure developers and investors. Still, the growth pattern is being more specialized, focused, and innovation driven. The local farms would now be able to create their own business models around scalable production versus volume targets, so that they would be able to target niche markets, premium segments, and differentiated produce.

For instance, high-quality leafy vegetables, premium seafood species and specialty food items, can also be productive markets without the burden of a set national quota. Government assistance for running the business efficiently is also better, including some subsidies aimed at saving energy, automating labour intensive work and implementing data-driven monitoring systems.

Farms implemented via robotics and AI monitoring, as well as sustainable power systems and more, to produce higher yields in a shorter period of time lead to reduced long-term costs. And startups and technology providers stand equally ready to expand. Now, the modified approach opens space to companies operating in areas such as controlled-environment engineering, aquaculture health diagnostics, agri-robotics, bio-nutrients and sustainable packaging.

Such businesses offer vital solutions that enable the industry to become more resilient and resource-efficient rather than going head-to-head if the volumes and volume of volume is a priority. Through the journey the ecosystem becomes wider, it has the opportunity to have a diverse list of sustainable systems.

Consumers and Evolving Food Culture

Consumers are also a key aspect of Singapore’s local food resilience strategy. New goals that promote increased knowledge of local produce, including how it’s grown, how it differs from imported alternatives and what consumers may be doing to support the ecosystem.

The growth of farmers’ markets, direct-from-farm delivery options, brand-related activities around local produce, and others, contributes to solidifying public awareness and appreciation of the importance of supporting local production. As cost efficiency improves and producers get bigger and more producers scale, consumers may find better pricing and a broader mix of local alternatives as well.

There are also subtle changes in Singapore’s food culture. Restaurants, cafés and meal preparation companies are promoting more of their items from fresh, locally grown ingredients. This trend also strengthens agri-food by maintaining a market for high-quality, sustainably grown food products, providing demand for agri-food as well.

These are changes that highlight the extent to which food resilience is not simply something you put into government effort, but is a mass-based phenomenon, made whole by consumers, chefs, companies, and innovators.

Shuffling the Road to a Sustainable Way 2030 and Beyond

The revamped “30 by 30” direction recognises that the global food landscape is changing. It will grapple with the problems of energy costs, land scarcity and labour limitations and pave paths for more creative, flexible models of local production.

But, at the end of the day, the mission is still the same: Singapore’s longer-term food security. In the years to come, we will observe ongoing experimentation, technological development, and ecosystem evolution. Farms will have smarter systems connected to the system.

New discoveries will be pushed by researchers. Investors will back sustainable solutions. And policymakers will adjust strategies based on the changing international situation. Revising “30 by 30” does not dull the nation’s determination; it reinforces it by ensuring that the goal is practical, attainable and connected to concrete problems.

With a more malleable and capability-driven roadmap, Singapore is in the process of creating an agri-food ecosystem that won’t just flourish by 2030, but for decades, ahead.